We Don’t Make Demands

Posted: September 11th, 2022 | Author: ucdcoc | Filed under: Disorientation Guide '22-'23 | Comments Off on We Don’t Make Demands

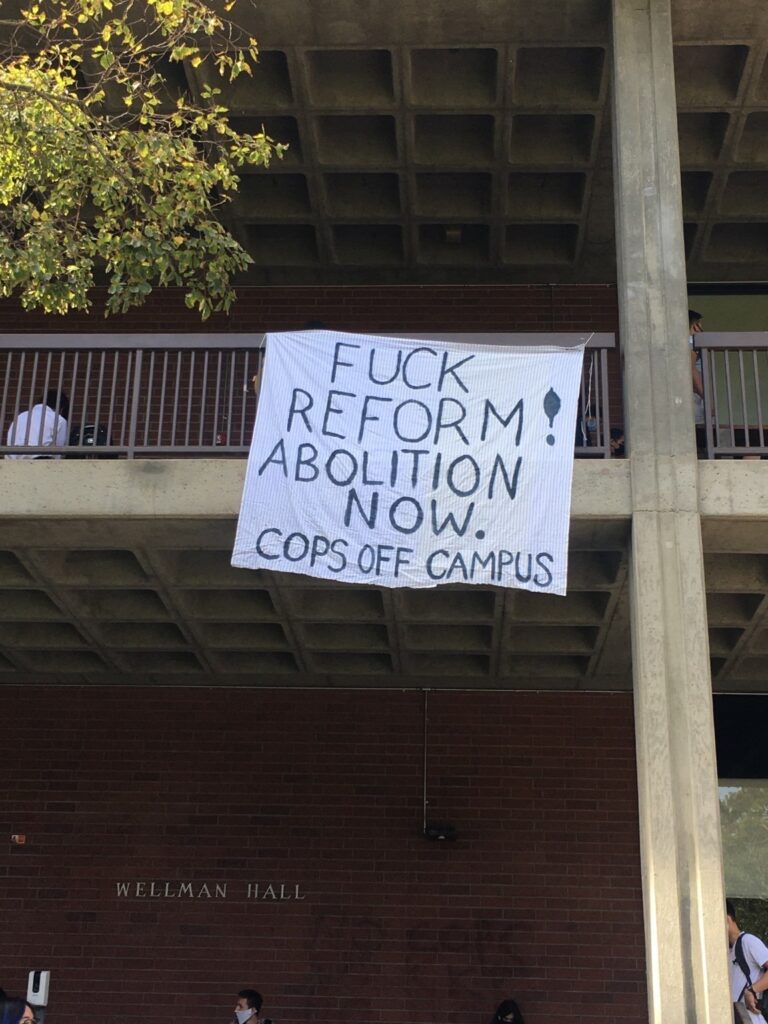

Cops Off Campus has never been shy about stating our aims. Indeed, our goal is right in our name: Cops off Campus — the immediate and total abolition of all forms of university policing. Yet we have never published a list of concrete demands. We have never explained how this should be done or provided a schematic for exactly what should come after. And this hasn’t been an accident. Our refusal to create a list of demands is a political choice.

UC Davis Cops Off Campus is committed to direct action; we are not interested in conversations with administrators who at any moment can call upon campus police to defend their positions. We’ve seen decades of discussion, listening sessions, task forces, strongly-worded statements, and promises to do better — all of these have led to nothing except the current record-levels of funding for campus cops. We know from experience that this route ends in failure, and that every day of failure is another day of violence against the most marginalized members of our community. It’s our determination to end this violence that has led us away from demands.

The logic of demands necessarily reaffirms the legitimacy of the administration

The affirmation of hierarchy is built into the act of making demands – one can only demand things from someone they believe has the power to grant them. Directing demands to a president, a chancellor, or even a department chair tacitly acknowledges their position of authority, and legitimizes it. We see no reason why administrators — who are essentially hired for their ability to fundraise — should be tasked with decisions about whether the campus community should work, live, and study with a militarized police presence. COC recognizes that the students who study and live on campus, the faculty and grad students who teach and conduct research here, and the community in which the university is set are more qualified to make decisions about what their safety means than are UC figureheads. Part of the logic of refusing to submit a list of “concerns” or “demands” to some university official is that we contest their authority, and we plan to relieve them of it.

We see their insistence that one “go through the proper channels” as both a diversion and an attempt to have us affirm their qualification to decide. And frankly, we find this insulting. We are the ones, after all, who have been brutalized, assaulted, followed, surveilled, and traumatized by the UCPD. We are the ones who track their violence and who have to insist that their focus and brutality is meted out disproportionately, overwhelmingly, on students of color, the disabled, those suffering mental health crisis, and the LGBTQIA communities.

Addressing demands to specific people or offices (the Chancellor, UCOP, etc.) would have us acquiesce to “the proper channels” — and in this case we recognize no other authority than those of the most marginalized on campus, whose safety and health is actually, verifiably, threatened by the presence of police. Moreover, the process of deciding the proper channels inevitably leads to a bunch of abstract questions about who is in charge, about what part of our overly complex and bloated administration would really be the one to “agree” to remove the cops. This is a demobilizing waste of time. COC’s refusal to address demands to various offices or administrators is therefore not only a refusal to accept the legitimacy of the administration and of university hierarchies in general, but also a practical decision about how best to direct our efforts.

Abolition is not an invitation to compromise; it’s a way to flourish

Demands that name specific mechanisms, funding structures, and time frames on the way to abolition invite reformist debates over policy. COC has a clear stance against engaging in task forces, policy discussions, and other reformist initiatives (for more info on why, you can read the statewide statement Against Task Forces). If COC were to name specific ways that we would like the administration to go about dismantling the police, we would be making policy proposals whether we intended to or not. In so doing, we would give the administration room to sidestep the problem by engaging with the details of each demand rather than with the larger issue of abolition. If we proposed moving money from one place to another over a specific time period, for example, we would inevitably be met with a chorus of quibbling and wonkery: “You don’t understand how university funding works. You can’t move money that has been earmarked for one thing to another account. This timeline isn’t realistic. We need more time to figure out how to implement this policy without causing disruption. We want to propose a different and less ambitious course of action. We are going to form a task force to study the feasibility of this proposal and will get back to you in two to three years. We are very committed to abolition.” The history of struggle at the university and elsewhere has shown that these debates are dead ends; the only way to avoid them is to avoid making demands in the first place.

Additionally, a list of demands gives administrators the space to present modest reforms as meaningful action. Presenting a concrete list of demands would give administrators leeway to meet (or partially meet, or promise to meet) one portion of our demands and then turn around and claim that they have listened and done their best. If our only “demand” is the total abolition of all policing on UC campuses, then there is no avenue for them to say that they have done what we wanted so long as the police exist.

Abolition is not Debate Team

Creating a list of reasonable demands makes it seem like we are trying to achieve our goals by convincing administrators (and others) of the soundness of our ideas. If history has taught us anything, it is that we cannot win through reasoned dialogue with the powerful. The abolition of campus police will not be achieved by convincing the administration of the feasibility of our demands, but through major disruptions to business as usual. In fact, making ourselves and our desires legible to administrators, or presenting ourselves as reasonable people with simple policy proposals, would suggest that our preferred mode of engagement is persuasion. It would reframe any direct action as a form of dialogue — a particularly flashy way to send a message — and place us in the realm of debate rather than action.

Discussion with those in power will always be a dead end, because no matter how thoughtful our arguments or how detailed our proposals, our enemies will never find us reasonable. The chancellor and administration are structurally on the side of the police. To say this is not to say that they are bad people or morally compromised in some way; it’s an analysis of their role at the university. The role of the chancellor is to ensure the smooth operation of campus by suppressing worker and student movements that threaten to undermine the university’s ability to profit (e.g. strikes for better pay) or otherwise challenge the way campus operates. This is true no matter what any individual chancellor believes — chancellors are successful at their job only to the extent that they can fulfill this role, and so are compelled to act as they do. And while chancellors have many methods at their disposal to quash worker and student movements (i.e. task forces, mediators, divide-and-conquer tactics, and communications offices full of spin doctors and propagandists), in the last instance their ability to do their job rests on the police. If every other method fails, they must be able to deploy the police to bring the campus back under their control. This means that police abolition cannot be a reasonable position to administrators — it threatens their very existence. You cannot force someone to know something that their paycheck depends on their not knowing. You can’t convince an administrator to abolish the police any more than you can convince the police to abolish themselves.

We will always seem unreasonable to those on the side of power. That is as it should be. Abolition is unreasonable within the framework that grants them that power. It is irreconcilable with the world as it exists, pointing instead to an entirely new world structured by different logics. If we ever begin to appear reasonable, it will be a sign that we have already ceded too much ground.

Cops Off Campus, Nothing Less

If we decline to make demands it is because we have chosen a different route. We are committed instead to acts of struggle, actions that we can all take together to bring us closer to a world without police. Even “Cops Off Campus” is not a demand as such. It is not a request pitched to administrators nor an invitation to compromise, but rather an articulation of our collective vision and a call to those who share our aims.