Posted: August 16th, 2025 | Author: ucdcoc | Filed under: General | Comments Off on Blaugust

What a strange summer it’s been.

In general, we are fond of the season. We’ve shared a long romance, one that’s spanned two centuries. Lately though, it feels as if it is coming to an end. As if the world and its dreamiest season, whom we loved for a time, has moved on, but too quick for our hearts to keep up, not yet free of the hope that we could see one another through the haze of those manic dog days one last time. We look outside, witness the occasional glimmer of possibility, only to see it fade with the quickness of its arrival. Then that awful dawning: what if all those flickers of euphoria, those moments that seemed inchoate beginnings, were, in the final instance, parts of a sequence destined for cataclysm? What if summer is over? Not like “See you next summer” over — like, really over.¹

This is all quite fanciful — as our departed comrade Joshua Clover wrote, everything ends. That’s a certainty. And anyway summer has always meant accepting the melancholy of its eventual end alongside its ecstasies. Perhaps what we are thinking through is simply an acute version of the allegory of autumn’s arrival. Perhaps precisely what we’re doing is summermaxxing. We are in a moment of great shifts, and we’ve yet to find our footing in this new atmosphere. If we’ve been quiet lately, it’s perhaps a reflection of the disorientation that seems to rule the moment. But let us stay anchored to our theme of summer’s twin languor and intensity. A brief cataloguing might ground us:

The year began with LA aflame. Spectacular, because LA is the world capital² of spectacle, but catastrophic nonetheless. Add it to the ledger of the decade’s horrors. Then summer came. LA aflame again. These, however, were flames of revolt. We let out a sigh of relief. Finally, the 5-year Thermidor had come to an end.

Or had it? Two months after the torched Waymos, we’re not so sure — Gaza is starving, the burn cycle has turned to flood, and ICE’s assault on immigrant populations remains as uneven as the resistance to it. The disorientation of the present is due precisely to this uneven character of catastrophe and revolt. The causes are global, but the effects seem to manifest locally; a flood there, a fire here; a raid here, a riot there. It’s both too much and too little. Is there a such thing as catastasistrophe? Does not roll off the tongue, do not like. One thing is certain: if the enemy prevails, the neologisms will be horrific.

We wish we had something like hope on offer. Pinned within the grips of blind optimism on the one hand, and We Are the Beautiful Losers-melancholia on the other, we would like to opt for a secret third thing. For now, it’s study. Summer is for blogging, and studying with comrades.

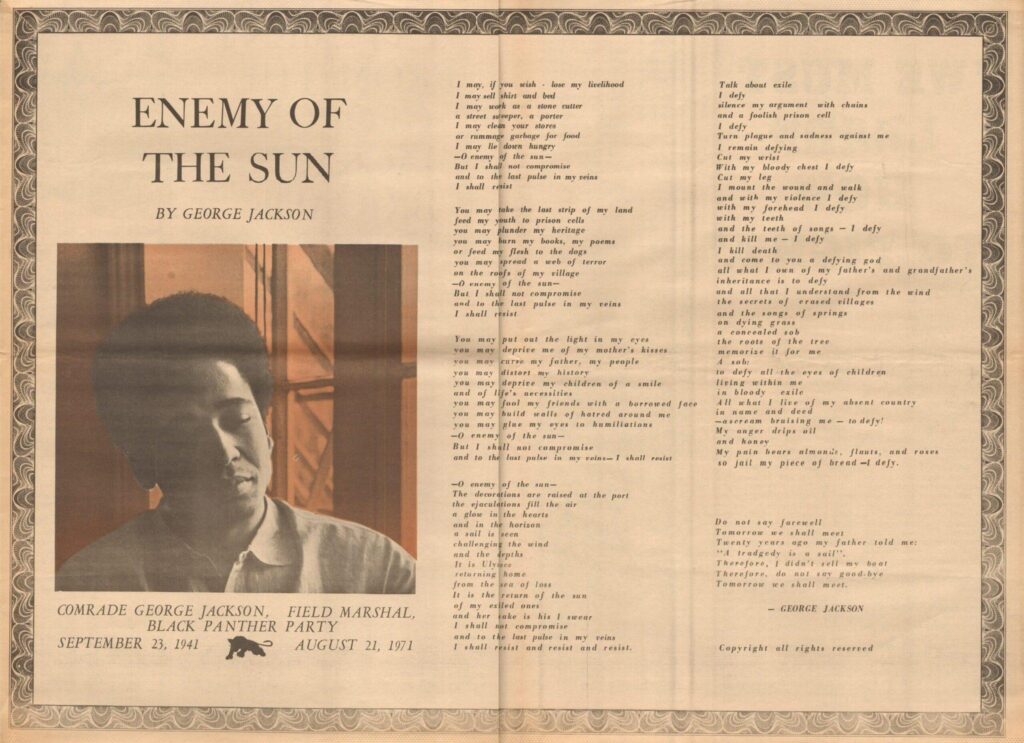

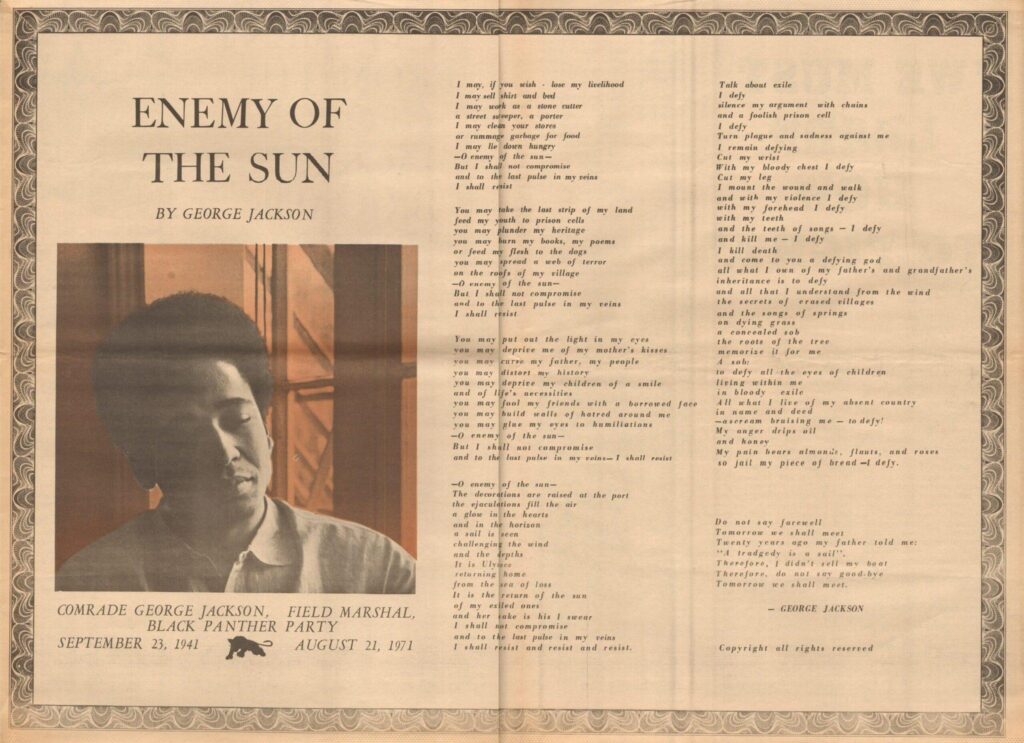

This Black August, as we approach the 54th anniversary of the Comrade George Jackson’s martyrdom, we turn to his example not via his prison letters, but the more directly revolutionary Blood in My Eye. We admire his erudition regarding the stakes of disarming police and military power in the U.S., his analysis of a “pig class,” as well as his brutally hilarious quips about cops. Like many other members of the black radical tradition, he took seriously the revolution in Palestine. Demonstrating this deep solidarity between struggles, we recently learned that a gorgeous poem titled “Enemy of the Sun” by Palestinian poet Samih Al Qasim was long misattributed to George Jackson after his Black Panther Party comrades found it in his prison cell following his death. (The poem is the featured image of this post.)

Ok fine we’ll leave you with one piece of feel-good news: a guy who works (worked) for the DOJ in DC recently chucked a Subway sandwich at a CBP goon. He fled but was ultimately arrested, upon which he said “I did it. I threw a sandwich.” Uncritical support for sandwich guy.

¹ If one were looking for evidence of the end of an affect, the pop charts wouldn’t be a bad place to look. Survey says that that summer feeling is curiously lacking this year.

² The fires were so vast in their destruction of highly-valued real estate that they caused losses in the European FIRE sector.

Posted: September 6th, 2024 | Author: ucdcoc | Filed under: General | Comments Off on From the Camp to the Campus: Reflections on the UC Davis Encampment

The worldwide mobilization in solidarity with Palestine defined 2024 for many campuses and communities. From the first tent pitched to the last one taken down — willingly or by force — many participants in and observers of encampments have written reportbacks and communiqués about how the encampments functioned, politically and practically, and where they encourage us to go next. With some of our members involved in the encampment at UC Davis, Cops Off Campus has wanted to offer its own thoughts. Recognizing that so many important points have already been made, though, we hoped to avoid replicating the work of others. So we decided to speak specifically as a group engaged in the movement to abolish police, in part because it is more clear than ever that all campus liberation movements are certain to encounter the police as a limit in their struggles, and in part because this has not been a perspective fully inhabited in the writings we have read (although of course police violence entered many encampments).

In supporting Palestinian liberation, we have seen how deeply connected are campus policing apparatuses to military entities abetting what happens in Palestine, from the two-way trade between the US and the Zionist entity in policing and surveillance, to the use of policing to repress dissent from their shared policy of genocide. We recognized how the forces of policing that pressed in on American encampments were always present, even when not spectacularly visible. We wanted to ask: what can that reality teach us about whether and how a movement in the imperial core can stand in solidarity with those fighting against their own genocide across the world?

The UC Davis encampment was set up on our main Quad, a flat, grassy space of a few acres, surrounded by various campus buildings including the main library, but not adjacent to the main administrative building. The encampment was a circular space with a perimeter of banners and fabric that grew in size as more students enthusiastically showed their solidarity and participated. Potential campers were asked to register (giving name and contact information) at a table set at entrances in the perimeter. Inside the encampment were medic support, mutual aid, food and water, and various forms of political education that – excitingly – featured instructors from all over Turtle Island. Like many other American encampments, the interior showed what a campus could feel like if it were a truly free space of education, basic needs addressed for all, tasks and chores shared by the community so everyone could learn together in a space of mutual care. And as a result, many connections of deep trust were forged through the interactions the encampment made possible.

Outside the encampment was the rest of the Quad, open to the entire university community and the public, around it on all sides. This configuration made the encampment visible and easy to approach. Most seeing and approaching the encampment came to show support. But the layout also made it easy for bad actors — Zionists, white supremacists — to roll up. Because the configuration was vulnerable to harassment and threat thereof, the encampment had its own security force posted at intervals around the outside of the circular soft barrier.

Seen and described this way, the encampment appears as a series of concentric circles, with the camp itself at the center and a set of circular barriers extending outward to protect it from harm. It also seems intuitive to understand the camp as a center from which sound, visual messaging, and action — politics, let’s say — emanated to influence and change what was around it, like ripples on a pond.

However, this set of circles can also be viewed in the other direction, from the outside inward, and from the least obviously visible to the most. The largest circle on campus is cast by the Chancellor, Gary May, a circle of abstract power executed by administrators, trustees, and regents who, as we’ll discuss, framed the encampment by regulating its strategies. Inside that circle were the various cop and para-cop forms that populate the campus: UCDPD, Core Officers, Student Affairs, anyone potentially deployed by the Gary circle to keep an eye on things. These cops never entered the camp itself and were largely invisible, but their representatives materialized readily outside when disorder seemed to loom. Inside that circle was what might then seem an entirely other order of security force, appointed by the camp itself. These were the aforementioned camp members who patrolled the outside of the camp circle. Reinforcing them in their task to keep threats out was the soft barricade surrounding the tents. And inside the soft barricade was the community space of the camp and the concrete circle that marks the center of the Quad, decorated with chalk messages for Palestinian liberation.

On the surface, then, power appears to move in two seemingly antagonistic directions – protest and disruption emanating outward from the encampment, and administrative power moving inward to stifle and contain it. However, the communication with administration that was built into the encampment’s structure resulted in these two directionalities of power cooperating rather than remaining opposed. This cooperation resolved the tension between antagonism and compliance on the side of compliance, such that even what was offered or perceived as opposition had already been caught up in the vector of the university’s overall mission: maintaining law and order.

In its approach to the outer edge of administrative power, the camp employed a demands-based political strategy. As Research and Destroy notes in their analysis of the encampment movement, this strategy places the camp within the admin’s regulatory parameters. As R&D continues, having a discrete set of demands was a feature of the national wave of encampments, focused as it was on winning divestment not exactly against but from the administration. They note therefore that having “specific and limited demands that must be won from an authority empowered to deliver them” required the encampments to both recognize and negotiate with that authority, treating the administrations as legitimate partners in a dialogue. In turn, the camps presented themselves as reasonable negotiators acting in good faith. The university and its administrators were therefore positioned as both adversary and ally, at once perpetrators of genocide and potential partners in opposing it. Although the list of demands originated from within the camp as a way to change the administration’s policies, that utterance ultimately redounded upon the camp, influencing their positions and actions and their effect on the larger surround.

The demand structure influenced many aspects of the encampment, even down to the community agreements that regulated life inside the camp. One of these agreements was that the camp was to remain police-free, with a sign near the entrance declaring that cops were not welcome. We wondered – does this mean that cops are not welcome here to harm us, or cops are not welcome here to help us? Was there a clear principle or was it pick and choose? Doubtless large numbers of campers, acting from abolitionist principles, did not want the cops to do either. At the same time, though, it seems likely that, for the cops to guarantee that they would not violently sweep the camp (which they never did), they would demand acceptance of collaboration, cooperation, and self-policing.

The parameters of what collaboration might look like were laid out on the first day of the encampment. In Gary May’s opening message about the encampment, he reassured the campus that his administration was “actively engaging the students to mitigate any disruption of campus operations, including access to classrooms, work areas, study spaces or residence halls.” This statement is followed directly by Gary’s insistence that UC Davis allows “peaceful protest” and will “not discipline students for speech protected by the First Amendment.” The juxtaposition of these two statements implies that free speech would be allowed so long as it remained speech only and did not disrupt the regular activities of the university. One is free to philosophize about the world if one promises not to change it. Moreover, the administration’s unremitting anxiety that campus movements might find themselves in communication, alliance, and coordination with other humans — referred to formalistically as “non-affiliates” and dishonestly as “outside agitators” — meant that the encampment, as part of the tacit détente with Gary and his implicit line of cops, was obliged to make sure no members of the public breached this encampment at a public university.

The administration’s role as both ally and adversary is clear here, with Gary May both the power that can send in the police and the power that can supposedly promise shelter against those same police, so long as the campers follow his rules. In the weeks following Gary’s first message, an uneasy truce emerged, in which the camp kept the peace and the administration refrained from sweeping it. This truce was vouchsafed by encampment leadership’s constant communication with Student Affairs and, through them, campus police. If the space within the encampment walls existed as a microcosm of a world without police, a quick glance over the walls reveals that camp leadership maintained this appearance only by integrating the encampment into the larger fabric of policing that surrounded them — by talking to administrators, cooperating with “campus safety” apparatuses, and agreeing to self-police. As some friends once wrote, “a free university in the midst of a capitalist society is like a reading room in a prison.” By the same token, a free encampment in the midst of circles of policing….

As vibes go, what radiated from the camp most of the time was a sense of peacefulness and useful activity. To preserve this status quo, the camp did not allow engagement with the counter protesters who showed up. The camp security team worked to “de-escalate” these situations, which involved ignoring counter protesters’ attempts to engage while monitoring them, documenting them, and preventing others from engaging in more militant defense. Campers were instructed to leave potential threats to security rather than responding themselves; defying the no-engagement rule could result in exclusion from the camp. Here again, the directionalities of power that maintained this sense of peace become important to notice. For one thing, the no-engagement rule originated from the encampment center but then emanated outward to legislate the behavior of people beyond the encampment itself all over the quad. For another, with the campers not permitted to participate in active defense themselves, policing – a defining function of the administration – became the condition of possibility for the camp’s continued existence, the alternative to broadly-based collective defense. And if this wider circle of policing was actual rather than theoretical – a kind of net to catch randos bobbing around in the open green space – then what else might it catch? Could it equally ensnare comrades acting autonomously to oppose the university’s complicity in the genocide?

In addition to the rule against engaging with counter-protesters, there was another rule, not written on any sign but no less binding: no escalation without encampment leadership’s permission. Importantly, this agreement did not just apply to encampment participants, but also influenced the entire campus community. In conversations inside and outside the camp, campers and their supporters heard that actions not approved by PULP leadership (and later UAW4811) would be denounced, leaving the perpetrators exposed to retaliation from administrators and encampment allies alike. Like the no-engagement rule, this rule both emanated from the center of the quad to affect the entire campus and reflected back an administrative priority. So when campus fell quiet for the duration of the encampment, with no major disruptions happening outside of its purview, many counted this state of affairs a successful camp-campus relationship for the rest of the system to emulate. All this despite the many calls for escalation flowing from Gaza and elsewhere.

The encampment’s disapproval of escalation developed in response to the specific conditions of the encampment. Escalation might risk breaking the uneasy truce with the administration, which would in turn encourage Gary to send in campus police. In the analysis of some encampment decision-makers, escalation increased the risk of police response, posing particular danger to marginalized and precarious camp members, and would potentially divert capacity and resources away from the camp itself. Direct action could also be blamed on encampment leaders, who would then receive the brunt of the repression regardless of whether they were involved. For these reasons, the possibility that someone might occupy a building or cause property destruction represented a threat, not to the administration, but to marginalized camp members. Risk aversion was effectively repackaged as community care, in a return of widely-discredited bromides best known as part of the Non-Profit-led liberal counterinsurgency during the George Floyd Uprising.

Of course, the notion that nonviolence successfully prevents repression is questionable at best; as we saw at many campuses across the country, administrators do not need an excuse to send in the cops. Certainly there is little support for the idea that policy-compliant protest gets the goods. However, given the spectacular displays of police violence that took place at Columbia, UCLA, and elsewhere, the encampment’s attempts to avoid repression were understandable. No one wants to see their friends brutalized by police or summoned by Student Judicial Affairs. At other campuses, Palestinians and other Arab students were targeted by administrators for retaliation, including suspensions and bans from campus, with those who were perceived as leaders often singled out for harsher punishment. It is also true that marginalized groups, especially people of color and trans people, face increased risks of police violence and mistreatment during arrest and detention. As we have written elsewhere, the question of how to act in response to the reality of differential risk is one that all liberatory movements must work through, and the UC Davis encampment was no exception.

Neither can Cops Off Campus be an exception, and as we continue to work through this question, we believe that the solution cannot lie in eliminating risk; it has to lie, we believe, in the willingness to take those risks together, in a genuinely collective way that involves the whole community and builds on the capacities each person in it offers. Solidarity is a vexed and, to some, even emptied-out term, but if it holds meaning for us, it is standing together to face risk and do what needs to be done. Solidarity to us means not only acting together disruptively but also acting together to defend those facing violence and repression. If the camp’s attitude toward collective risk was one factor that led it toward collaboration and compliance, then maybe a different approach to risk is called for, one that allows us to better stay outside of administrative control.

That kind of collective approach to risk allows for attack rather than collaboration. It might seem at this point that we are talking about “escalation,” especially since this was what the camp sought to prevent. But this term, too, has drawn critiques, and so we want to think a little more about what we mean. Escalate is a word derived through back-formation from escalator, which was coined by the Otis Elevator Company to market its moving staircase. It is a trade-word, a word of department stores, the end of flânerie at the hands of inexorable transactionality. So instead of using it, we’re going to tear into its segments like an orange and pull out its ancient seed: scale. We approach the different forms of attack that collective risk allows us not as escalation, then, but as experiments with scale.

Scale is a staircase and scale is a measure that can keep moving outward or inward. To scale out means, for us, disrupting larger parts of campus, treating the encampment as a base, not a space, and attacking in ways that exceed whatever bounds the largest circle of the administration may attempt to set. One familiar principle of abolitionist discourse has become its emphasis on building things up rather than breaking them down, a talking point that allays fear, that mitigates the sense of risk. But the breaking down has to happen for the new worlds to be realized fully. In this process, it seems important to take physical, material space that the university’s daily operations need – the staircase, the building – but attack is at the same time not just about taking the space, about territoriality. Attack means not only creating and defending alternate spaces, but generating force to push beyond them against the next layer that needs to be toppled and destroyed. Thinking about strategy spatially in this way might also mean asking whether radiating from a center, or even from multiple points considered centers in some way, will accomplish these ends.

Scaling out also directs us to the networks of solidarity that exist beyond our campus, connecting the encampment movement to the larger struggle for a free Palestine. This broader vision is most apparent when we consider the international scope of this struggle – the fact that we must act in solidarity with people on the other side of the globe – but it also applies to those directly outside the university’s walls, whose exclusion through policing defines the university as a separate space. These larger networks make possible autonomous actions taken by students and nonstudents alike. For example, when an anonymous group attacked the UCOP building, they did so independently of any encampment, yet their actions intensified the encampment movement’s exposure of universities as enablers of genocide. If any movement is to grow into a mass mobilization equal to the scale of the horrors it opposes, it must eventually be taken up by people its originators have not met and may never meet. These people will necessarily act autonomously, calibrating their strategy based on their own capacity and local conditions. To grow, a movement does not have to be centralized; it can embrace these autonomous actions as the vehicle by which the struggle can spread, even when these actions assume risks and face repression that other formations within the movement are unwilling or unable to do themselves. Scaling out beyond ourselves asks us to embrace those who scale up the intensity of attacks against genocide, to celebrate those willing to take necessary risks, and to support those who face repression. Being part of an international movement asks us to support the most radical elements of our own movement so as to better reflect the scale of violence and bravery of struggle happening elsewhere.

For those of us at the encampment, the weeks spent together were a time of collective growth and learning, and we forged bonds of friendship and trust that have lasted beyond the camp’s dissolution. If you participated in the encampment, whether you attended a single teach-in or stayed for the duration, you became part of a community and saw a glimpse of another world, however fleeting. Now that the camp is over, the connections you made in that space can become the foundation for taking further action together. As part of the movement for a free Palestine, you are now connected to thousands of people you have never met, in Davis and around the world, who will have your back when you decide to act. What would it mean to take those relationships, our connections to comrades known and unknown, and carry them forward into the fall within a framework of attack? We hope that the coming year will see bigger, bolder attacks on the university and its deathmaking. May the struggle generalize until there is no space that can contain us, until all walls and borders and checkpoints finally fall.

We’ll see you out there.

_________

We welcome the sharing of the above text online, but also at distros, demos, your local radical bookstore, etc. Here are print versions for reading and for printed zine formatting:

PRINT

READ

Posted: June 28th, 2022 | Author: ucdcoc | Filed under: General | Comments Off on FREE LUNCH PROGRAM

May 18, 2022, University of California Davis

The usual protocol for entering the dining commons at UC Davis requires students to swipe a card deducting from their meal plan while others pay cash or other method. On May 18, during the midday rush, a banner hung from the outdoor balcony of the Latitude Dining Commons declared a FREE LUNCH PROGRAM. Though the administration often performs concern over the high measure of foodinsecurity among students, they did not arrange Wednesday’s free lunch. Rather, a group in solidarity with the police abolition movement gathered in front of the swipe station and invited everyone to eat for free. And eat they did. The action had support from other campus and community activists and groups committed to police abolition, mutual aid, and workers’ rights. A banner dropped from above the hall’s entrance demanded, FEED THE PEOPLE / COPS OFF CAMPUS.

What does free food have to do with cops? In the wake of the action, a small group of young republicans pretended to be baffled by this matter. The shortest path to clarity might involve paraphrasing Kwame Ture: If someone wants me to go hungry, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to make me go hungry, that’s my problem. The police are the power to make people go hungry — when there is enough food to feed the campus, the city, the state, the planet with ease. But this is not what the institution wants. No matter what it says, its actions brook no confusion. And so, fully aware that deploying the pepperspray boys would be a bad look, they sent instead a small platoon of administrators to try to stop things. Everyone knew the police station was two blocks away. The situation was tense. “You can have a protest,” said the most cringing of the well-compensated snitches. “But you can’t say ‘Free Food.’ Can we find some sort of compromise?”

Yes, absolutely. The compromise was: free food but everyone would try not to laugh at the admin.

The students walked in, a few bemused, many relieved, some a combination of the two. As word got around, some non-students came as well. The university likes to call them “non-affiliates” and pretend they are a threat to the university community. We think they are people, as deserving of food as anyone.

As observers, we see in this event a model for transforming the university. It is an act of community care, egalitarian and open-hearted. But it is not an act of philanthropy, requiring the grace and largesse of donors much less of other poor people. Charity shifts the pieces on the board a little in order to keep the game fundamentally the same. Those who own much might be generous though it is those who own little who are asked to donate over and over. A university’s goal must be to own nothing. The abolitionist message of a dining hall takeover is that we want an entirely new and different structure, a making-free of the resources that should be — that are — ours in the first place. Swipe-free, tuition-free, police-free, we are not joking about a free university. Administrator-free too, just as a cherry on top.

But we recognize certain things about actions that take this form, that turn toward liberation rather than donations, free education rather than gofundmes. Acting against the protocols of the university means taking risks. The group inside Latitude comprised undergraduates, graduate students, alumni, faculty, and community members. They represent different levels of vulnerability to aggression and punishment because of status within the university, socioeconomic situation, race, gender, disability, or a combination of these and other factors. The group attended to these differing vulnerabilities by standing side by side around the card swipe counter, confronting the risk together and committed to responding together, just as they will stand in solidarity with anyone who is persecuted for their presence that day.

Previous dining hall actions, especially those at UCSC during the COLA wildcat strike of 2019-20, inspired the Latitude action. At UCSC, the administration unleashed significant punitive force on the activists. UCD COC doesn’t know if this university plans to get carceral on a group that made one free meal possible on a campus with a 44% food insecurity rate and a posse of administrators protecting their own wealth. But we hope you will support us if they do. More importantly, COC hopes you will ask yourselves and others why the basic human need for sustenance is policed here and how together we might make food free every day for everyone.